Getting Started with Windows Defender Application Control (WDAC)

Windows Defender Application Control (WDAC), formerly known as Device Guard, is a Microsoft Windows secure feature that restricts executable code, including scripts run by enlightened Windows script hosts, to those that conform to the device code integrity policy. WDAC prevents the execution, loading and running of unwanted or malicious code, drivers and scripts. WDAC also provides extensive event auditing capability that can be used to detect attacks and malicious behaviour.

Configuring WDAC

WDAC works on all versions of Windows, however, prior to Windows 10 version 2004 only Windows 10 Enterprise had the capability to create policies. I used Windows 10 version 2004 Professional to create this blog post.

On a supported OS version you can deploy the default Windows WDAC audit policy with the command:

ConvertFrom-CIPolicy -XmlFilePath C:\Windows\schemas\CodeIntegrity\ExamplePolicies\DefaultWindows_Audit.xml -BinaryFilePath C:\Windows\System32\CodeIntegrity\SIPolicy.p7b

The DefaultWindows_Audit.xml is a reference policy supplied by Microsoft that can be used as the base to build a more customized policy. The DefaultWindows_Audit.xml is designed to only allow the base operating system. This includes WHQL-approved drivers and anything in the Microsoft App Store. The AllowMicrosoft.xml policy would allow all Microsoft signed code and applications, such as Office, Teams, Visual Studio, Sysinternals, etc, which I personally consider too permissive.

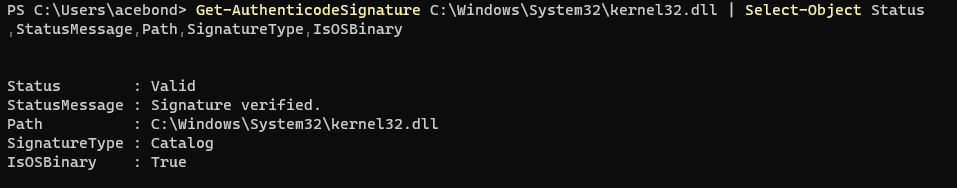

An important distinction should be made between Windows and Microsoft signed code. Windows refers to the base operating system while Microsoft refers to any code signed by Microsoft. The Get-AuthenticodeSignature cmdlet can be used to determine if a binary is part of the base operating system.

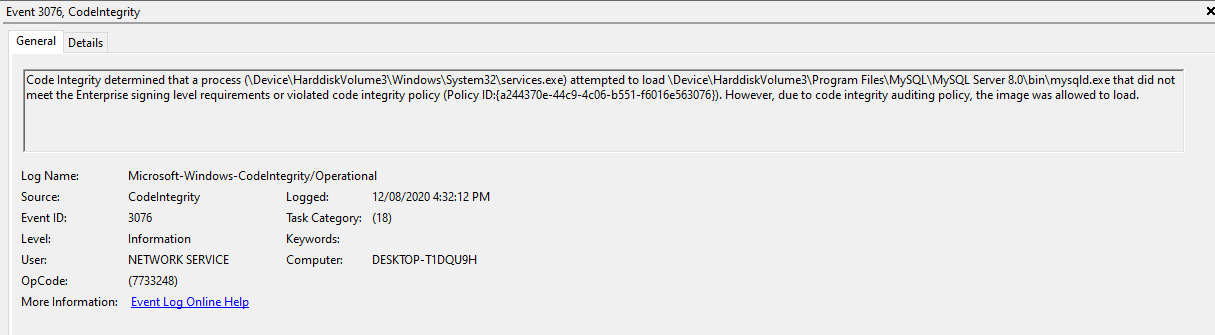

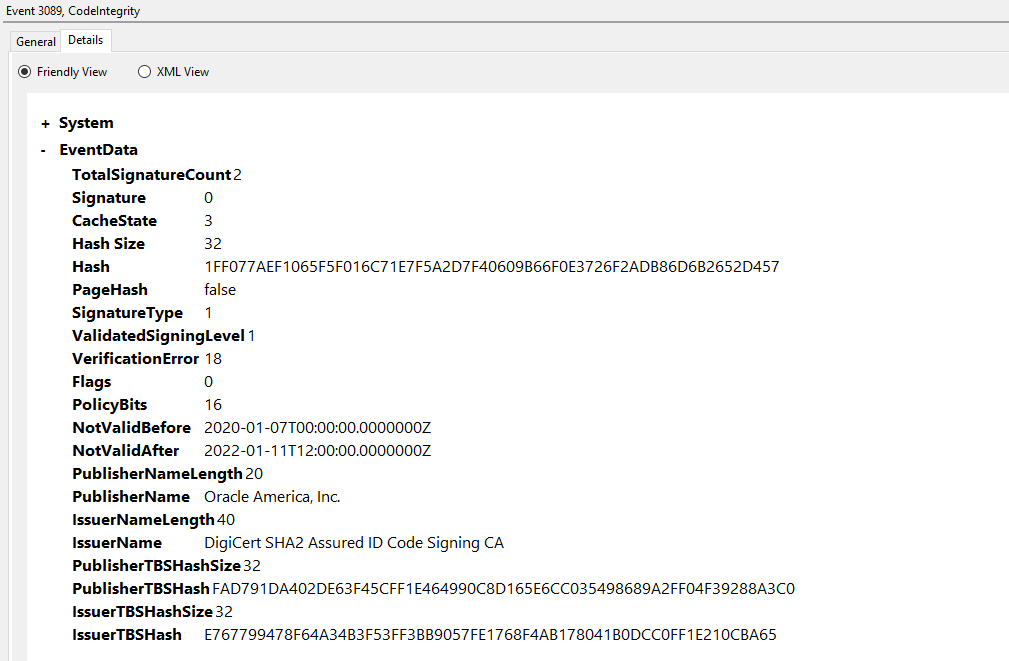

After enabling the DefaultWindows_Audit.xml policy with the above command and rebooting, the event log can be used to inspect code integrity violations. The events will be stored in the Applications and Service Logs Microsoft Windows CodeIntegrity Operational log. The Event ID 3076 represents a code integrity violation in audit mode. These events will be followed by at least one Event ID 3089 which provides further information regarding the signature of the binary in violation. The 3076 and 3089 events can be correlated through a Correlation ActivityID viewable within the raw XML.

The example Event ID 3076 below shows that services.exe loaded mysql.exe, which did not meet the code integrity policy.

This violation produced two 3089 events, as is evident with the TotalSignatureCount of 2; the first, Signature 0 (displayed below), shows that mysql.exe had a digital signature from Oracle.

The last signature, which will always exist, is a hash created by WDAC using some internal hashing method.

Whitelisting Software

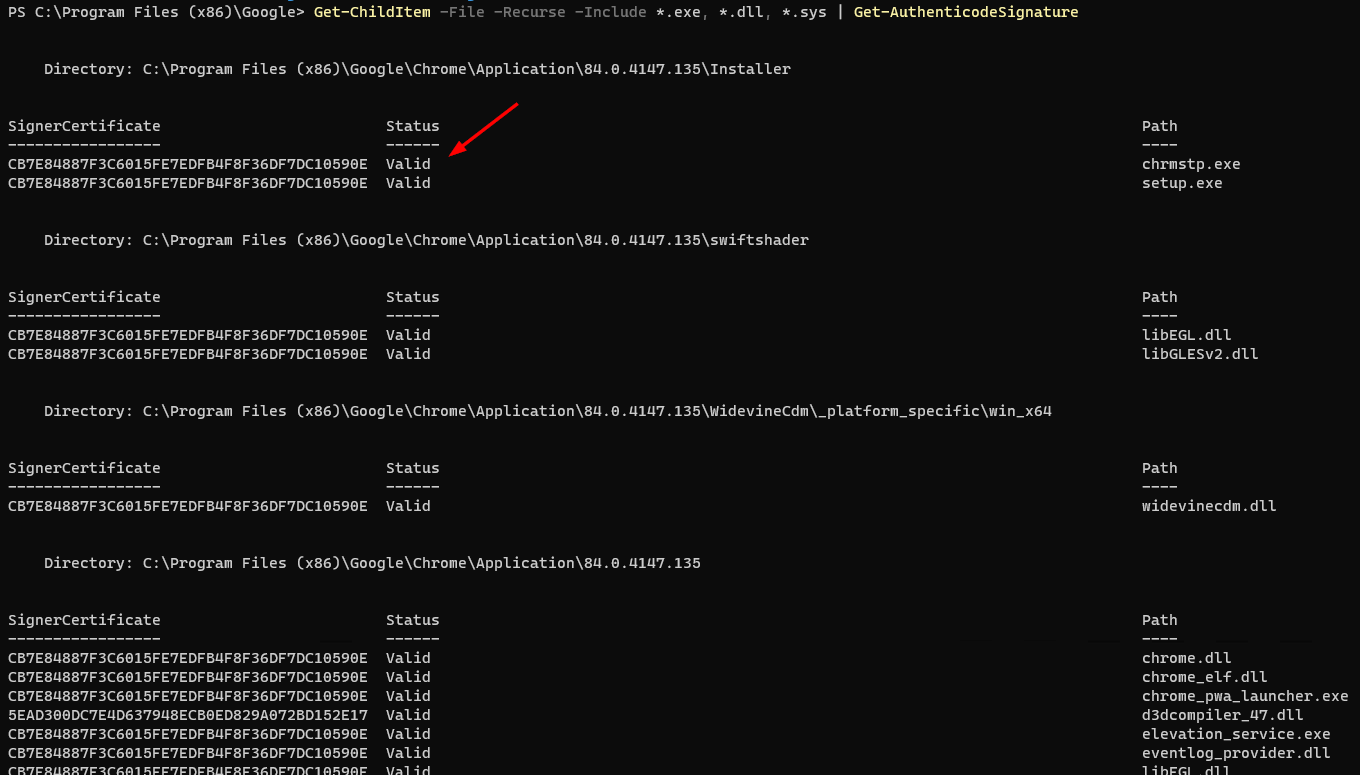

I’m going to demonstrate creating a code integrity policy for Chrome, 7-Zip and Sublime Text 3. First, let's examine the Chrome executable files with the command:

Get-ChildItem -File -Recurse -Include *.exe, *.dll, *.sys | Get-AuthenticodeSignature

The results show that all of the Google Chrome executable files are signed with a valid signature.

The Chrome policy can be built based on the Publisher using the commands:

$SignerInfo = Get-SystemDriver -ScanPath . -NoScript -NoShadowCopy -UserPEs

New-CIPolicy -FilePath Chrome.xml -DriverFiles $SignerInfo -Level Publisher

The name of the cmdlet Get-SystemDriver is misleading, since it's also designed to collect the information needed for user mode policies, and is not exclusive to drivers. The information from Get-SystemDriver is then used to create a new policy based on the Publisher level.

The rule level specified in the Level parameter is extremely important and specifies how code is authorized. The Publisher level is a combination of the PcaCertificate level (typically one certificate below the root) and the common name (CN) of the leaf certificate. This rule level allows organizations to trust a certificate from a major CA, but only if the leaf certificate is from a specific company (such as Google LLC). This is lenient in contrast to the Hash, or FilePublisher levels but reduces the maintenance overhead as it allows Chrome to update itself, and even add new files, that will continue to be trusted assuming they are signed using the same certificate. The full list of rule levels are part of the WDAC documentation.

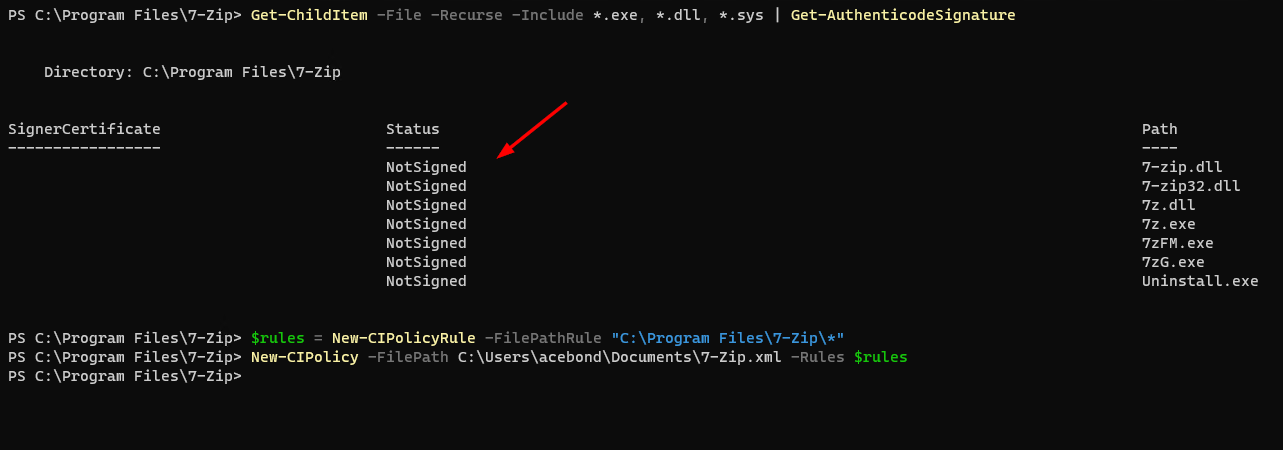

While performing the same process on 7-Zip I discovered that none of the executable files are signed. In this instance, I could create a policy that whitelists each file using the Hash rule level which “specifies individual hash values for each discovered binary”. I have opted the less secure approach of whitelisting the 7-Zip folder to demonstrate feature parity with AppLocker.

$rules = New-CIPolicyRule -FilePathRule "C:\Program Files\7-Zip*"

New-CIPolicy -FilePath C:\Users\acebond\Documents\7-Zip.xml -Rules $rules

The 7-Zip code integrity policy is based on the FilePathRule and allows all code in the 7-Zip Program Files directory. The wildcard placed at the end of the path authorizes all files in that path and subdirectories recursively.

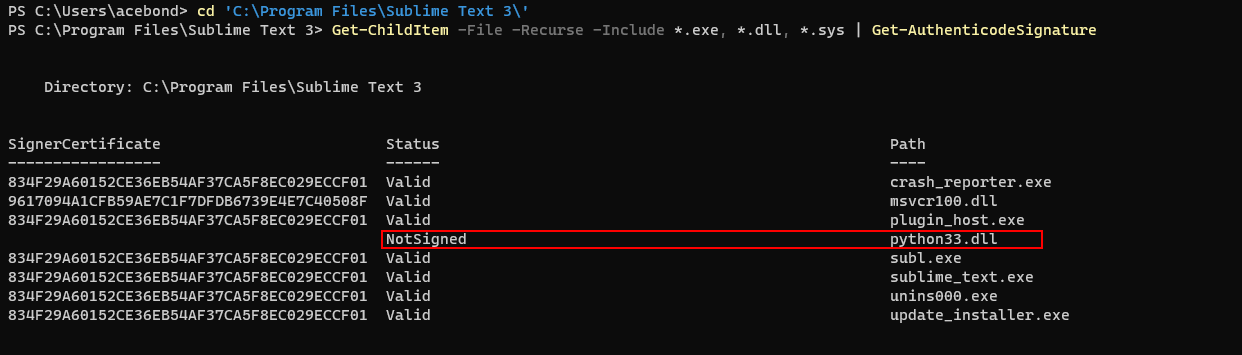

Sublime Text 3 contained a mixture of signed and unsigned files.

In this instance, the Fallback parameter can be used to specify a secondary rule level for executables that do not meet the primary trust level specified in the Level parameter. I chose to trust the Sublime Text 3 files based on the FilePublisher which is a combination of the FileName attribute of the signed file, plus Publisher. Files that cannot meet the FilePubisher trust level, such as python33.dll, will be trusted based on the Hash rule level.

$SignerInfo = Get-SystemDriver -ScanPath . -NoScript -NoShadowCopy -UserPEs

New-CIPolicy -FilePath Sublime_Text.xml -DriverFiles $SignerInfo -Level FilePublisher -Fallback Hash

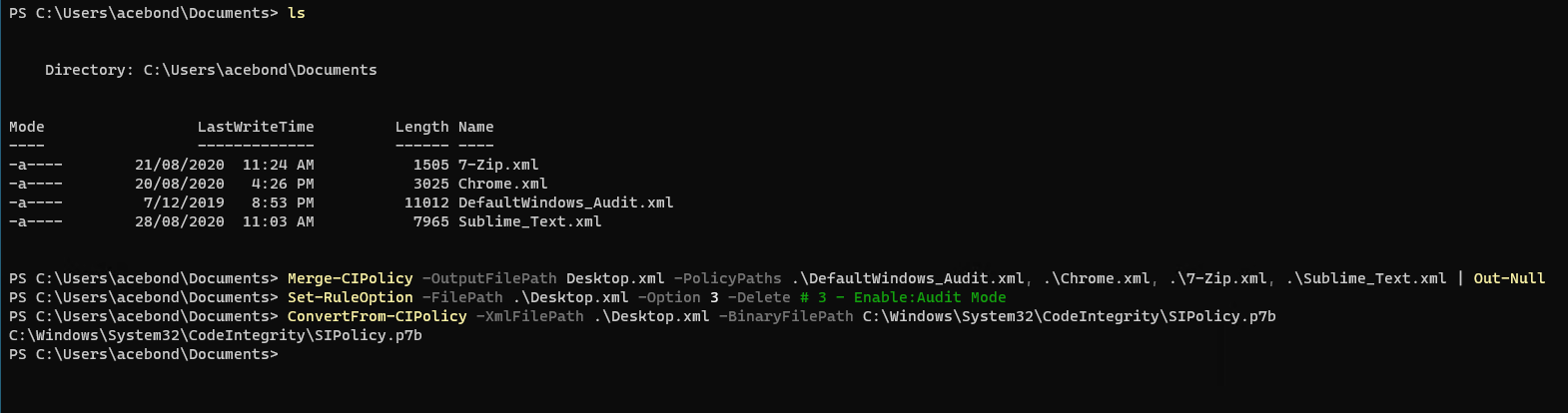

These 3 new policies can be merged into the base DefaultWindows_Audit.xml policy to whitelist Chrome, 7-Zip and Sublime Text 3. In the screenshot below I have merged all 4 policies. A quick note that Merge-CIPolicy uses the first policy specified in the PolicyPaths as the base, and does not merge policy rule options.

I have chosen to live dangerously and removed rule option 3 (Enable:Audit Mode) so the policy executes in enforcement mode.

Copy-Item "C:\Windows\schemas\CodeIntegrity\ExamplePolicies\DefaultWindows_Audit.xml" .

Merge-CIPolicy -OutputFilePath Desktop.xml -PolicyPaths .\DefaultWindows_Audit.xml, .\Chrome.xml, .\7-Zip.xml, .\Sublime_Text.xml

Set-RuleOption -FilePath .\Desktop.xml -Option 3 -DeleteConvertFrom-CIPolicy -XmlFilePath .\Desktop.xml -BinaryFilePath C:\Windows\System32\CodeIntegrity\SIPolicy.p7b

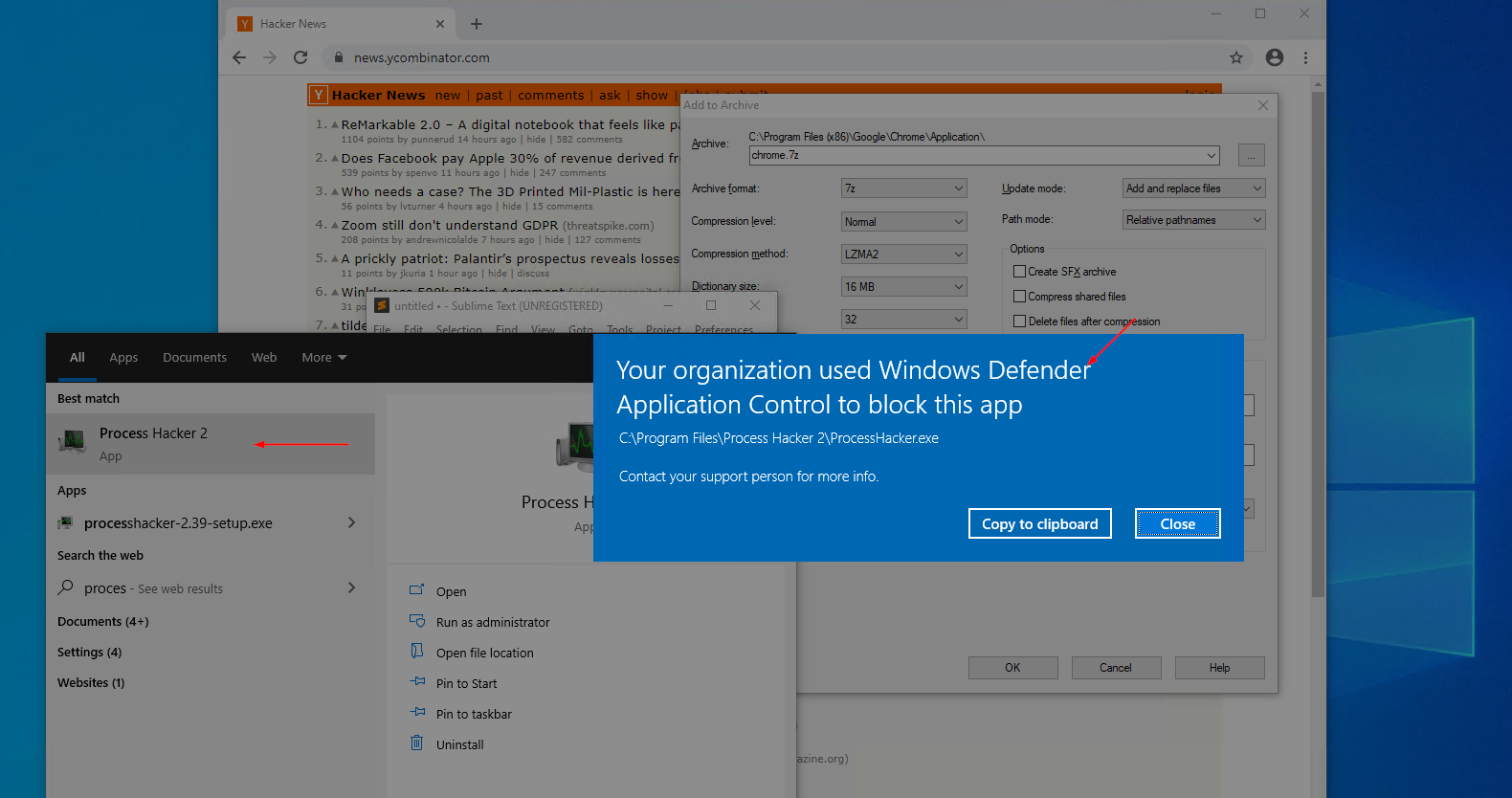

The new policy allows Chrome, 7-Zip and Sublime Text 3 and blocks all other software from running.

Bypassing WDAC?

WDAC is a security boundary that cannot be bypassed without an exploit. The only practical method to bypass WDAC is to find a misconfiguration within the organisation policy. This could be a whitelisted folder, certificate authority, or software component.

The example policy created in this blog post contains a number of leniencies that can be leveraged to circumvent WDAC. Firstly, the 7-Zip policy allows all code within the 7-Zip Program Files directory. A privileged user could place files in this directory to bypass WDAC and execute arbitrary code. Generally, WDAC policies should never whitelist entire directories.

Secondly, Sublime Text 3 comes packaged with Python which is a powerful interpreter that can be used to bootstrap the execution of arbitrary code. All software within a WDAC policy should be reviewed for scripting capabilities. The risk can either be accepted, the software removed, or in some cases the scripting functionally removed.

Lastly, the policy does not block a number of default applications built into the OS that allow the execution of arbitrary code. A list and policy to block these executables is maintained in the Microsoft recommended block rules.

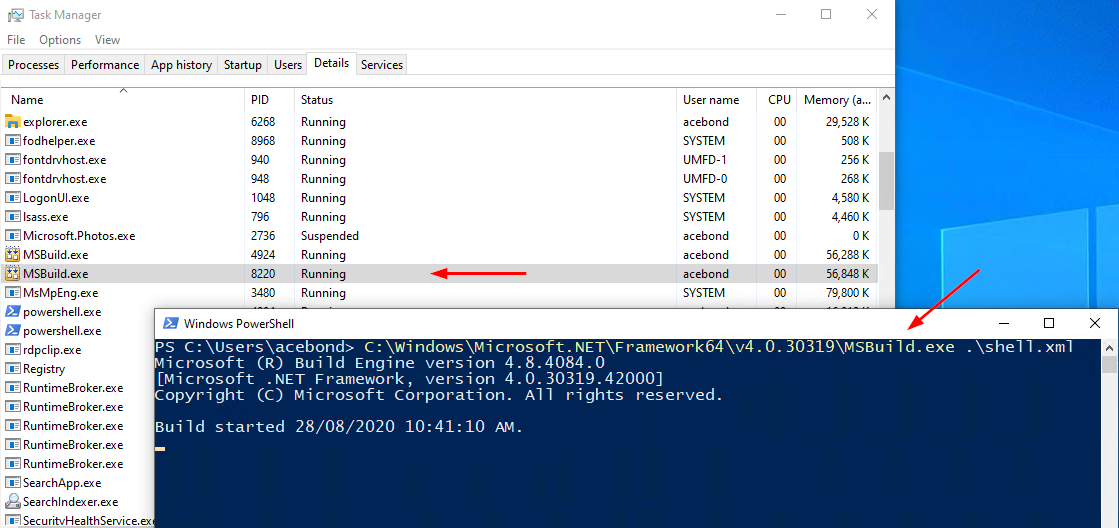

To demonstrate, I’ve used the well known MSBuild executable to execute a Cobalt Strike trojan and bypassed the WDAC policy. The MSBuild.exe executable will load a number of libraries to compile and execute the code provided, but all of the executables and libraries involved are part of the base operating system and code integrity policy. This is not a WDAC vulnerability, but rather a misconfiguration in that the policy allows an executable that has the ability to execute arbitrary C# code. These are the types of executables that create holes in application whitelisting solutions.

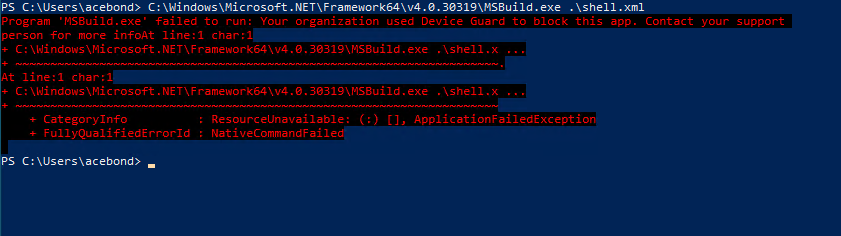

The MSBuild bypass, and all Windows executables that bypass WDAC can be blocked by including the Microsoft recommended block rules in our WDAC policy. A number of these executables do have legitimate use cases, and I personally think the focus should be on monitoring and initial code execution methods, as running MSBuild.exe implies that an attacker already has the ability to execute commands on the system.

I saved the block rules as BlockRules.xml. If the policy is designed for a Windows 10 version below 1903 then you should also uncomment the appropriate version of msxml3.dll, msxml6.dll, and jscript9.dll at Line 65, and 798. After deploying WDAC with the additional block rules, MSBuild cannot be used as a bypass.

Benefits of WDAC

WDAC prevents a number of attack scenarios that other solutions cannot. The following advantages of WDAC are in comparison to AppLocker, although most will be true for any application whitelisting solution.

WDAC prevents DLL hijacking since only code that meets the code integrity policy will be loaded. This effectively mitigates all DLL hijacking attacks since any planted DLLs will fail to load and create an event log that should be investigated immediately.

Privileged file operation escalation of privilege vulnerabilities (for example CVE-2020-0668and CVE-2020-1048) cannot be weaponized. These types of vulnerabilities use a privileged file operation primitive to create or replace a binary in a privileged folder such as System32. WDAC prevents the vulnerabilities from achieving code execution since new or replaced files would violate the code integrity policy.

WDAC can be applied to drivers which run in kernel mode. This prevents tradecraft that leverages loading a malicious driver to disable or circumvent security features. My previous blog on Bypassing LSA Protection could be prevented using WDAC although Credential Guard is a better solution.

Code integrity policies can be applied and enforced even on administrative or privileged users. With a solution like AppLocker, there are hundreds of methods available that an administrative user can use to circumvent, hinder or disable the functionality. A correctly configured WDAC policy, cannot be tampered with by an administrative user, even with physical access. This can be achieved with Hypervisor-Protected Code Integrity (HVCI), Secure Boot, BitLocker and disabling the policy rules Unsigned System Integrity Policy and Advanced Boot Options Menu.

WDAC is a security feature built on security boundaries that are guaranteed to be serviced by Microsoft. AppLocker is great, but it's designed for when you are using application control to help users avoid running unapproved software, and is not designed as a security feature.

Getting initial code execution on an endpoint device is one of the most difficult phases during a red team engagement. As such, malicious or unintended code execution on a device should be treated as a security boundary. Preventing code execution from taking place in the first instance is one of the best defensive actions that can be implemented within an organisation.